The eyes which see reality: four short films with non-human perspectives

by Ben Nicholson

‘Since we cannot change reality, let us change the eyes which see reality.’

Nikos Kazantzakis, Report to Greco.

Sebastian Mulder’s documentary NAYA – Der Wald hat tausend Augen opens with an explanation of its subtitle, which translates literally as ‘the forest has a thousand eyes.’ On-screen text explains that it is part of an old German hunters’ expression in which you are never alone out in the wild, because where one pair of eyes stares into the forest, a thousand eyes stare back. In Mulder’s film, the meaning of this saying is flipped; the film’s “wild” – the eponymous wolf, Naya – is stared back at by the myriad “eyes” of electronic surveillance. The non-human eyes of the wolf are met by those of camera lenses, deployed by people to watch on their behalf. The juxtaposition and interplay between human and differing non-human perspectives form an interesting vein running through four short films in the Square Eyes catalogue: Janaina Wagner’s Curupira and the machine of the destiny, the aforementioned NAYA, Nicolas Gourault’s VO, and Jeppe Lange’s Abyss.

Wagner’s decision to adopt the perspective of a spirit, allows for an otherworldly aspect to possess the audience via reflections and apparitions conjured from layered images.

Curupira and the machine of the destiny may seem like something of an outlier in this quartet as it is the only one of the four that doesn’t examine the implications of a mechanical viewpoint. Instead, the audience is guided by the ghost of a 14-year-old prostitute, Iracema, as she hitchhikes to meet the demon Curupira, protector of the Amazon. The character of Iracema is taken from Jorge Bodanzky and Orlando Senna’s 1974 film Iracema: Uma Transa Amazônica, which was initially banned by the military regime for both its explicit imagery and its social commentary about the poor treatment of people and the forest. While Wagner’s film may be more enigmatic in its critique, it is no less powerful.

Filmed on two highways – the BR-319 (the “Phantom Road”) and the BR-230 (the “Transamazônica”) – the settings themselves are like wounds cleft through the Amazon, the land a victim of a determination for economic exploitation. Wagner’s decision to adopt the perspective of a spirit, allows for an otherworldly aspect to possess the audience via reflections and apparitions conjured from layered images. As Iracema ventures into the forest to meet Curupira, we seem to be given access to a deep time that lies before the plundering of the landscape and beyond mere human perception.

Quite what the implications are of Iracema’s meeting with Curupira remain mysterious, but a line of narration that bookends Nicolas Gourault’s VO could almost have been referring to it. Describing the experience of relinquishing control to a non-human agent, the voice claims it was ‘absolutely terrifying… but exhilarating.’ The situation could hardly be more different – he is discussing the action of taking his hands off the steering wheel in a self-driving car – but Curupira and VO have more touchpoints than might at first be obvious. In Curupira, the non-human ghost of Iracema perceives the world around her being carried in vehicles controlled by people. In VO, people are carried by vehicles that control themselves and perceive the world around them.

The visual return of the cameras in NAYA might be somewhat more literal than in VO, but they are similarly being deployed in lieu of human eyes.

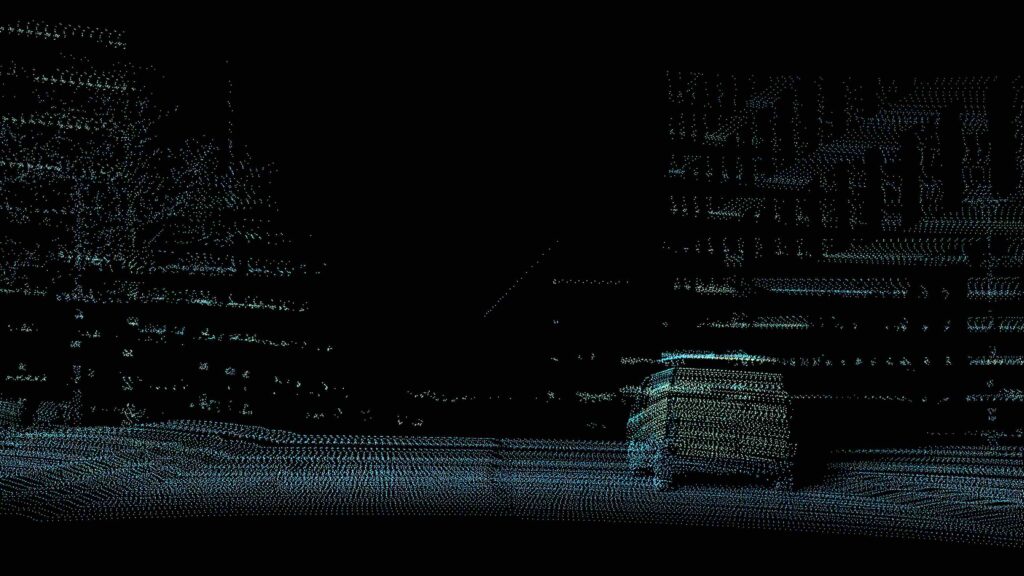

Gourault’s film is built around a single tragic accident involving a self-driving car and a pedestrian but expands from that point to be about the nature of computer drivers and role of human workers in the development and testing of the vehicles. Gourault’s somewhat essayistic treatment of the subject combines newsreel footage about the accident, video footage captured by the vehicle’s camera, and the impressionistic digital landscape that the car itself could “see.” As the voices of workers recall colleagues becoming very trusting of the car’s capacity to manage itself, the screen presents shifting, spectral sketches that emulate the cars’ attempts at deciphering their environments.

The visual return of the cameras in NAYA might be somewhat more literal than in VO, but they are similarly being deployed in lieu of human eyes; their job is to keep a stoic watch out for GreyWolf680female, or Naya. GPS tracking has determined that she has travelled from Northern Germany and settled in a certain area of Flanders in Belgium, but nobody has spotted her. Mulder’s film mixes visualisations of data sets with various modes of found footage; from surveillance cameras and time-lapse recordings to camera traps, used by conservationists and hunters alike, and primed to capture evidence when they sense movement.

Suddenly, after a reported sighting, images that previously featured cameos from only mice, deer, and badgers make way for humans, dogs, and gunshots. Snippets from local radio shows chart the story shifting from the emotional return of an animal in an area from which they had been absent for centuries, to the warnings of hunters that say they’ll shoot Naya if she gets too close. After several attacks on livestock, Naya is suddenly framed as a ‘beast,’ and the camera footage seems to transform into the CCTV on a crime watch program. In the final chilling images, the eyes originally trained on recording Naya’s movements in fascination, seem to have been co-opted into her hunt and persecution. The non-human eyes may remain neutral, but their use is anything but.

To some extent, Abyss feels like the fourth cardinal point on a compass of different interpretations of non-human perception. [...] It is a study in how similar the manmade lens’s discernment of likeness is to our own.

In VO, at one point one of the interviewees says, ‘They tell you “Don’t trust the software, never trust the software.”’ Jeppe Lange’s Abyss doesn’t just ignore this advice, it actively rejects it – Lange shares the directing credit with Google’s Image Recognition AI. Abyss allows machine learning to take the driving seat in presenting a hundred-mile-an-hour (or perhaps more accurately, 13-image-a-second) montage in which each static image is selected for its visual resemblance to the last. This may sound like a lot to take in, but the very instruction given to the AI means that the film moves in undulating waves of theme, form, and colour. In the gaps, we’re left to search for our own interpretations or connections. Some of these might prompt a smile, like the jump from the faces of domestic cats to those of lions that will surely please cat lovers everywhere. Others – like the intermingling of religious paintings of various faiths – highlight our similarities, more than our differences. Most strikingly, some moments seem to suggest the beginnings of a similar visual language to our own – in particular, the cut from a close-up image of a vagina to the stamen of a flower evokes a visual symbolism rife in human art history.

To some extent, Abyss feels like the fourth cardinal point on a compass of different interpretations of non-human perception. Where Curupira narrates a quest for an ancient, more-than-human way of seeing, Abyss is a study in how similar the manmade lens’s discernment of likeness is to our own. If VO seeks to illustrate the dangers of an over-reliance on the mechanical eye, NAYA explicitly depicts the equally terrifying consequences of human action in response to the images produced by that eye. Lange’s film at least feels refreshing in that it finds hope, beauty, and indeed comradery in the non-human perspective, but the other films in this selection might serve to remind us to be careful not to become too complacent.

_____

Ben Nicholson is a writer and curator based in London. His words have been published in Sight & Sound, MUBI Notebook, Little White Lies, The Guardian, and Hyperallergic, amongst others, and he is also a contributing critic and the lead shorts reviewer at The Film Verdict. He has been involved in programming for Sheffield Doc/Fest and the London Short Film Festival and in 2019 founded ALT/KINO which screens, and publishes writing about, experimental film and artists’ moving image.