Cruising Oblivion: Tim Leyendekker’s Feast

by Marcus Jack

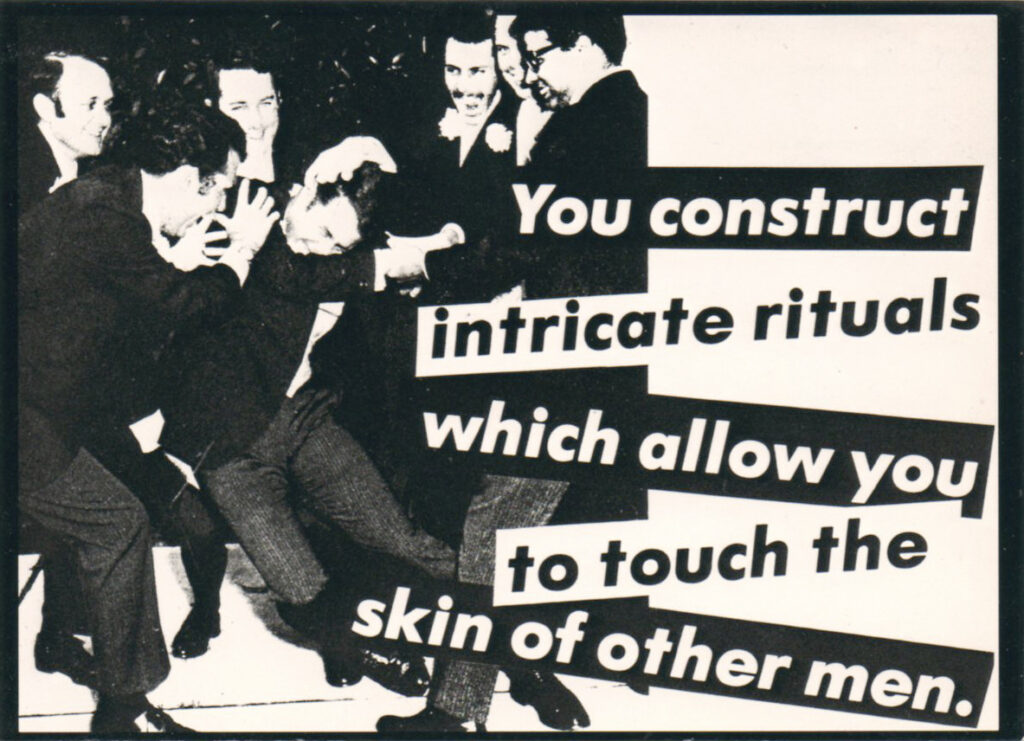

Shot too close or too dimly, something happens to skin processed through the low-fidelity digital image. The epidermis blisters in clouds of static, separating into a sickly green and magenta. When the camera pulls back, just a little, this grain coalesces enough to briefly reveal a grey-pink knuckle, an armpit, the arch of a back. The ambiguity of these fleshy parts is betrayed only by their familiar motions—tensing, twinging, releasing. Dutch artist-filmmaker Tim Leyendekker’s first feature Feast (2021), written with theatre director Gerardjan Rijnders, is punctuated by these erotic abstractions: flurries of skin, hair, thighs, fields of red like strong light filtered through an eyelid. Exceeding the camera sensor’s capacity to capture fast-moving shifts in gradient and saturation, these stuttering images are only approximations of something more organic, more complex. Opening the 85-minute work, they set an intention as the first of many Brechtian devices which draw attention to the construction of narrative and image, in both the film itself and around its sensationalised criminal subject, the Groningen HIV case. The camera which crudely rationalises form and colour into staccato waves offers a fitting analogue for our ill-ease with moral ambiguity, with non-binarised thinking.

In 2008, three Dutch men—Peter M, Hans J and Wim D—were convicted of grievous bodily harm after injecting fourteen others, then drugged and semiconscious, with HIV-infected blood at gay sex parties hosted between 2006 and 2007. Feast unsettles the moral inference of this abhorrent headline and its dualities: of victim and perpetrator, of submission and dominance, of good and bad, of sickness and health. Orbiting the crime are seven fragments shot in in collaboration with seven cinematographers—Benito Strangio, Adri Schrover, Reinier van Brummelen, Boris van Hoof, Claire Pijman, Aafke Beernink and Robijn Voshol. Atom-like, each of these particles, a different texture and mode, augments the others, developing a holistic, layered and more open-ended account.

“In its wry juxtapositions, this list—spoken plainly—exposes something of the banality of evil; atrocity, served with mixed nuts and soundtracked by campy house anthems.”

In the first, a police official steadily unpacks three trunks of evidence, laying items on the table before the viewer. “One used condom; eleven unused condoms; two unused condoms, extra-large; one dildo, penis; one dildo, fist; six compact discs, Kristine W – Feel What You Want, George Michael – Ladies & Gentlemen,” she continues, “three bottles of GBH, 250ml.” In its wry juxtapositions, this list—spoken plainly—exposes something of the banality of evil; atrocity, served with mixed nuts and soundtracked by campy house anthems. In another vignette, actors dramatize an imagined scene between the three perpetrators, pacing the mise-en-scène of an immaculate yuppie apartment whilst musing on a definition of Eros—is love the subjugation of oneself to another? An attempt to deny death? The pursuit of oblivion? Invoking Plato’s Symposium, itself a drunken banquet attended by men, Leyendekker sutures the incriminating orgy to the philosophical forum. In a second Brechtian reveal, the orators are watched from behind a one-way mirror by another group of analysts, played by the same trio.

Truth and fiction are further intermixed by a consecutive pair of interviews. In the first, those erotic images of skin reappear, disintegrating and reforming, whilst audio of a real conversation with Hans J conveys a deep remorse. In the second, footage of Peter M, cropped and silhouetted to protect his identity, offers a recalcitrant counter. Made villainous in his refutation of guilt, the scene unravels as lines are repeated, amended, and the backlighting which bestows anonymity gives way to the slow illumination of an actor’s face. Troubling the efficacy of this documentary trope, Leyendekker again exposes the techniques through which narrative is established; the moral framework stutters.

Perhaps the most disquieting revision offered by Feast, however, is a seemingly gentle provocation to rethink pathology at its core. In the fluorescent light of a research laboratory, plant biologist Katerina Sereti demonstrates how tulips if subject to certain viruses will become co-dependent and inextricable. The pathogen and host collaborate in mutations that alter the flower’s colour, from yellow to red, a process which can be trained to enhance diverse attributes across flora. Viral infection is here presented as neither good nor bad, neither healthy nor unwell, it causes a neutral augmentation of biological states which only through context and interpretation is accorded moral judgment. If transferred to the Groningen case, as the viewer is compelled to do, this logic prompts an uncomfortable reappraisal of the criminal pathogen. For Peter M, or his dramatic stand-in, an HIV-positive status offered the key to social, sexual and spiritual ascent, brokering community, “a form of belonging with others who are the same,” and freedom, “because then everything is possible.”

“the film is an exercise in challenging fixed, homogenous moralities and the means through which the film form conspires in their upholding”

Feast is not a defense of its central violence, nor does it seek to trivialize the severity of permanent infection and ongoing disease management conferred upon fourteen men without consent. In its penultimate sequence, we meet a victim, Max, undergoing police questioning, faced with a blaming, psychoanalytic response supplied by heteronormative values which cannot seem to parse the erotic from the deviant, the pleasure from the pain. The suffering of these men is unequivocal. Instead, the film is an exercise in challenging fixed, homogenous moralities and the means through which the film form conspires in their upholding. It advocates for the preservation of ambiguity amidst the drive to rationalise, for a multiplicity of positions, modes and truths that reckon with the dominant social paradigm of binary thought. The skin is neither green nor magenta; the camera makes it so.

_____

Marcus Jack (he/him) is a curator and writer based in Glasgow, Scotland. He recently submitted his AHRC-funded PhD thesis, “Artists’ Moving Image in Scotland: Production, Circulation, Reception, 1970–2021,” undertaken at The Glasgow School of Art, and is currently a visiting researcher with the Archive/Counter-Archive project at York University, Toronto. Jack is the founding editor of DOWSER (2020–), an open-access serial about artists’ moving image in Scotland, and in 2015 founded Transit Arts as an itinerant platform for the support of artists’ filmmaking. He has written for the ICA London, MAP Magazine, Videoclub, Open City Documentary Festival and LUX Scotland.