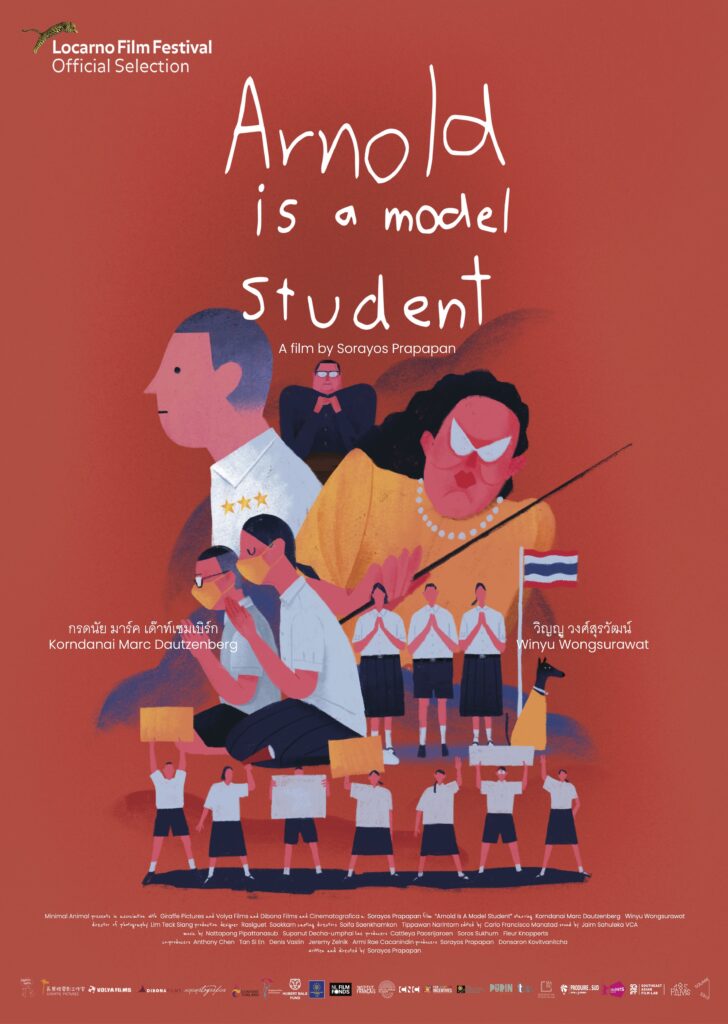

Not a Healthy Model: Sorayos Prapapan’s Arnold is a Model Student

by Ren Scateni

In his early shorts, Sorayos Prapapan honed his wry and succinct style. The international film industry and Thailand’s social structures are under scrutiny in films like Dossier of the Dossier (2019) and Fat Boy Never Slim (2016), which respectively comment on the precarious conditions to which filmmakers are subjected when trying to get their projects funded and the compulsory military service for young Thai AMAB individuals. Dossier of the Dossier, in particular, is about a filmmaker-producer duo whose application for funding for their first feature has been turned down by a fictitious film fund body called Cinemarket – IFFR CineMart, is it you though?!

Eight years in the making – and supported by multiple organisations including IFFR Hubert Bals Fund, the Centre National du cinéma et de l’image animée, and the Singapore Film Commission – Prapapan’s feature-length debut, Arnold is a Model Student (2022) is the result of a script that has been revised and updated to reflect on Thailand’s fast-paced political scenario and the anti-monarchy protests that gained momentum in the country in 2020 and 2021. Today, it’s tempting to read Dossier of the Dossier as Prapapan’s biographical eulogy to a missed opportunity to rack up money to work on what would then become Arnold is a Model Student.

The eponymous Arnold is a cocky and witty high school student who was recently awarded a gold medal for Mathematics at the International Academic Olympiad and went to the United States to study for a year. His excellent scholastic curriculum and privileged social background marry with an apathetic and opportunistic stance towards both the educational and societal turmoils Thailand is going through. When, around him, students begin to organise and protest the strict regulations and abuse they suffer at school, Arnold singles himself out and instead joins a cheating racket to help candidates with poor grades to pass governmental exams. Prapapan is never judgemental of Arnold’s actions; instead, the filmmaker offers an ambiguous albeit incisive portrayal of youth in times of a wider historical crisis.

The film’s visual grammar thrives on juxtaposing the rigid, cage-like nature of the school’s mandates and the adrenaline-filled messiness of real-life manifestations of dissent.

Arnold is a Model Student is based on the “Manual on How to Survive School” by the Bad Students Movement, whose activity began in 2020 and is still operative today. The movement was born out of the need for students to challenge the authoritarian rule of teachers in school. Thailand’s educational system is bound by strict regulations some of which hark back to the 1970s when the country was under the military dictatorship of Thanom Kittikachorn. Prescriptions include military-style hair and other rules about hair length, gendered uniforms and dress codes banning any individual expression of identity and style. Physical punishments are of course integral to the country’s scholastic apparatus. Textbooks are also severely impacted by the monarchist line with key events like the October 1976 massacre of pro-democracy students led by far-right paramilitaries entirely glossed over.

Prapapan tesselates Arnold is a Model Student with excerpts from a facsimile copy of the Bad Students manual weaving an organic, chapters-driven narrative throughout the film. Some pages read, “Students have the freedom of expression. Teachers must not threaten the students or use their authority to force them into submission,” or “School should be a safe place”. Scene after scene, Prapanan shows us how bribed Thailand’s education system is and how the teachers and the head of the school alike are trapped in vicious institutional inertia. Similarly, Arnold’s apparent indifference and privilege shield him from active socio-political involvement. Prapapan’s sedate style is matched visually by the filmmaker’s static and symmetrical framing, especially when it comes to surveying the school environment. Such unassuming naturalism is contrasted by phone-shot documentary footage of pro-democracy protests either shot by the filmmaker himself or other protesters who then uploaded the videos online (consent was sought before including them in the film). The film’s visual grammar hence thrives on juxtaposing the rigid, cage-like nature of the school’s mandates and the adrenaline-filled messiness of real-life manifestations of dissent.

Other real-life references permeate the film. In one of the film’s early scenes, a boy named Sorayos Prapapan is being punished by a teacher while a hidden nod to section 112 of the Thai Criminal Code regulating lèse-majesté is dropped mostly for Thai audiences to pick up on. Later on, parallels are drawn between Arnold’s father – a teacher admonishes Arnold not to follow in his father’s footsteps, who was kicked out of the country – and Yan Marchal, a French national and resident of Thailand for almost 20 years, who was denied re-entry because of his anti-monarchy social media posts. Nevertheless, the film’s lighthearted tone never forays into camp, as Obayashi Nobuhiko’s anti-fascist scholastic tale School in the Crosshairs once did. Here, no ego-driven Venusian alien wishes to mind-control humans and enforce his autocratic rule; instead, it’s the down-to-earth dictatorial reality of a country that coerces and limits youth’s individuality and freedom.

Ren Scateni (they/them) is a writer and curator interested in experimental and artists’ moving image works, whose writing has appeared on ArtReview and ArtReview Asia, Hyperallergic, MUBI Notebook, and Sight & Sound among others. Ren is Head of Programme at Encounters Film Festival and a Trustee of Alchemy Film & Arts.