“The world behind the eyes”

Interview with director Viktor van der Valk

Where does the idea for the film originate?

I think around the time of my thesis film, ONNO THE OBLIVIOUS (2014). You’ve graduated, you’ve been prepared for a brand new world, a new start, and it’s a moment of maturity. It’s the moment you’ve become a director. But all I thought was: is that me? What have I actually learned over the past four years? At most, I now knew how to look at film, how to work with it. I noticed I was struggling with two different worlds. One that exists solely in my head, which I call the world ‘behind the eyes’, and the other right in front of them, a kind of reality. The world ‘behind my eyes’ includes my thoughts, my desires, my dreams and fantasies, my ideas and a whole array of fragments that pop up randomly. What takes place ‘in front of my eyes’, is a reality that I would often childishly deem disappointing: a future of taking responsibility and working for money.

I realized that I didn’t quite know how to relate to either of these worlds. I think that’s what me and co-writer Jeroen Scholten van Aschat bonded over, a shared struggle that seemed to be inherent to our stage of life. So, in a way, you could say this a classic coming-of-age story. At least, this was the starting point for an idiosyncratic story with poetic ingredients. Language rarely suffices when trying to identify things, which is why I reach for forms of poetry, to leave room for interpretation.

Language rarely suffices when trying to identify things, which is why I reach for forms of poetry, to leave room for interpretation.

As much as language falls short in the film, everybody still continues talking.

At a certain moment, it dawned on me how this film is my attempt to capture my mind from the inside out, to observe it in action, almost in between sleeping and being awake. It’s in that state of mind that thoughts and lines of dialogue simply occur to me – without stopping. That can be wonderful, but it can also drive you mad. Especially when you’re in the middle of a creative process and it just keeps overwhelming you. That’s what I’ve tried to capture through film.

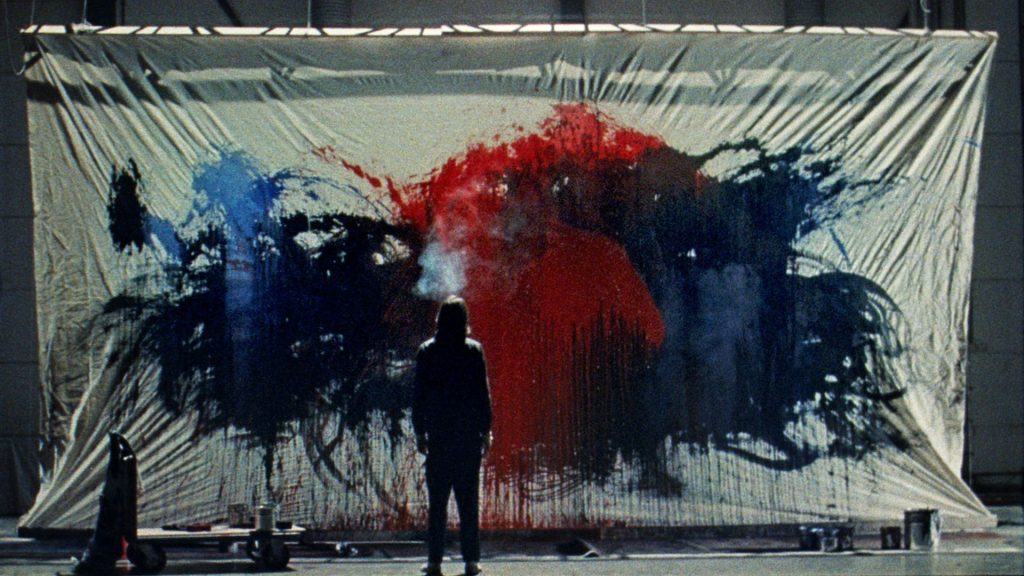

The meta-element in NOCTURNE is that director Alex aspires to that very same thing, but that the world ‘in front of his eyes’ forces him to make it more concrete, more tangible.

Seen from the producers’ and investors’ points of view: absolutely. Alex struggles with the commercial side. He asks himself: why are we pointing our arrows that way? There’s another side he ignores, one that has less to do with filmmaking. With my short film ONNO, I’ve set out to make a film that could be some kind of band-aid to the whimsicality of everyday existence. With NOCTURNE, I realized too late that film sometimes needs life as well. You have to dare to look at life in order to be able to imagine it. I’d forgotten that. I had to make this to be able to focus on other people again, to look at the world around me again.

The film has echoes of Federico Fellini’s 81⁄2 (1963); that film speaks of a filmmaker’s doubts, dreams and nightmares as well.

I’m not a big fan of Fellini, but I do think 81⁄2 is a masterpiece. Co-writer Jeroen and I have watched it repeatedly. Yet, we kept asking ourselves: what use is this to us? Won’t it be pretentious if we set out to make a film about a filmmaker’s search? But we thought: fuck it, we’re talking about the guys who haven’t arrived at anything yet! Where’s your mind at if you’re a nobody? Don’t you have the same kinds of doubts? Does it make any difference whether you’ve acquired a certain status or not? It’s always your prerogative to speak of whatever truly concerns you.

NOCTURNE is an eclectic collection of images that plays around with close-ups, color, image, dialogue, text and sound. How did you go about that?

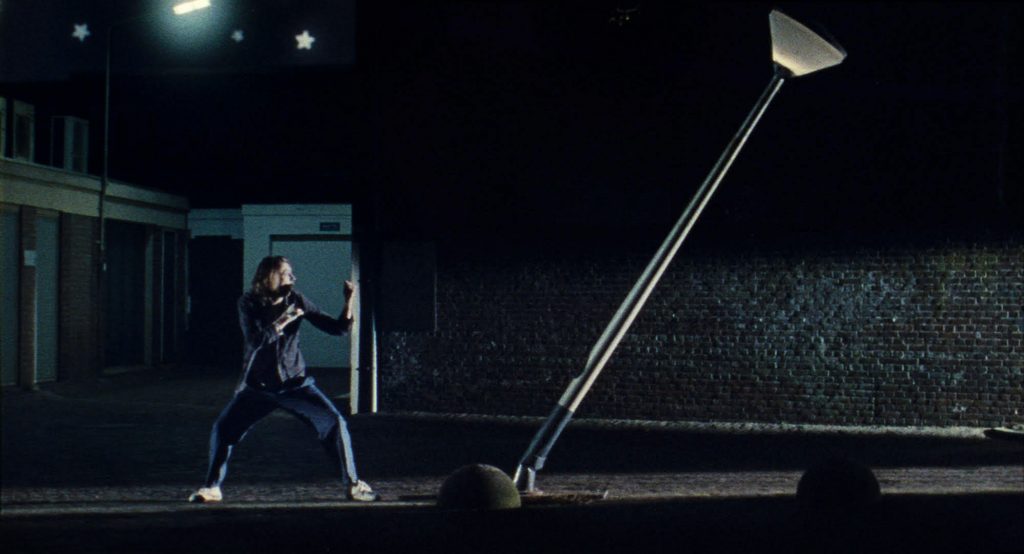

We started shooting with a kind of unfinished screenplay. The script at the time was, obviously, far too big and ambitious, but we’d already agreed on shooting dates. So I had to cut pages of screenplay as I was already making shot lists and talking to the production designer. We had agreed on the most important rule of the game: NOCTURNE is all about a guy who has two realities intermingle. He’d prefer to live in a romantic, cinematic reality – but he’s a dejected type of guy, so his idea of romance is a rather dilapidated one. That’s what we set out to find, but our budget put restraints on us. Sometimes, we used close-ups simply because we couldn’t afford to design and shoot a wider world. It makes you go: fuck, another close-up. It’s the eternal battle between money and freedom.

Those close-ups do enhance the strange, sometimes very intimate atmosphere running through the film. Added to that is the fact that all the actors often whisper. It’s got something playful to it, as if everything’s a fantasy.

I cherished a strong desire to look at film again the way I did when I was little. Back to the days when I made little short films with my brother Vincent. Even though that was just an act of play,everything also felt highly important all the same. That’s the feeling I had to convey to my actors. How will we talk and act if everything has to be suspenseful all the time? Because everything’s important! This film is the equivalent of what I feel when I’m lying in bed and thoughts just occur to me. You almost miss out on one because the next one already seems so important. The whole film had to maintain that kind of energy. I thought it would go well with all the film noir elements throughout the film.

The cast consists of a remarkable ensemble of familiar faces from both the Dutch and the Belgian acting worlds. Part of your own family is involved in it, too. Why did you gather this particular group of people?

It all started with Vincent. When we were young, we had an unspoken agreement that we would make our first feature-length film together one day. I thought the material called for him to play Alex. After that, I started thinking about what I’d need from the rest of the cast: a certain type of speech and a way with words, first and foremost. I looked for actors with a kind of musicality to them, a kind of rhythmic flow. This resulted in a wishlist of actors we called up immediately. Even though most people were enthusiastic, some had no time to join, and others thought the screenplay too vague, which it actually might have been. In the end, we were lucky that most of our favorite choices ended up agreeing to be in the film.

An especially funny thing about the scenes between Vincent van der Valk (“Alex”)and Reinout Scholten van Aschat (“Ferdinand”) is that they look so similar.

I knew Reinout because we made a short film together – BRICK (2013) – during my time at the Netherlands Film Academy. Plus, he happens to be co-writer Jeroen’s little brother. Throughout writing the screenplay, we started playing with the idea that Alex would need an alter ego, a character who could embody the other side, the side of ambition and obsession. So I thought: who actually resembles Vincent? It so happened that, once upon a time during an exercise at the Maastricht Theatre Academy, Reinout actually impersonated Vincent – and, according to legend, he did so fantastically.

Franz Schubert’s unfinished symphony seems to weave like a thread through the film. Where did that come from?

I only discovered this piece’s importance later on. My dad is a timpanist in the 18th Century Orchestra. As a child, I often joined him at his concerts. In the beginning, I was obviously bored to death and uninterested, but it got into my system regardless. Along the way, I started to actually enjoy it, and it even resulted in me using classical music in my films. For example, during an exercise at the Film Academy, I’d play a classical piece in order to find inspiration. This type of music seems to almost force me to use my imagination, to simply surrender to my thoughts. Sometimes, my dad would share with me what music he and his orchestra were rehearsing. One time, as I was writing NOCTURNE, he gave me this Schubert piece. I played it and was immediately hooked. It starts with a dark kind of suspense. It’s almost like a journey to me, but it has fairytale-like undercurrents as well. It’s also very melancholy and romantic. When I read that Schubert never actually finished this symphony, I realized it fit perfectly with a film that would never be truly finished and would continue to be completely imperfect. I just had to use this music; I wrote it into the screenplay, and I even timed certain shots to the music when we filmed them.

You just said the film would never be truly finished; do you really think so?

It will be complete in its incompleteness. I don’t mean that as a poor excuse, but I secretly truly wished to make something imperfect. I feel I’m light years away from being able to make something perfect. Then why wouldn’t I embrace it being imperfect and frayed? In that sense, this film is unfinished. We’ve mostly used NOCTURNE as a platform for thoughts, fragments and ideas. We’ve been raised with the idea that film is a way to tell stories. That’s a possibility, and that can be beautiful, but it can also limit our curiosity for what else and what more film can be. Maybe that’s what I’m looking for.