Angelo Careri in conversation with the directors of Knit's Island

Where did the idea of making this film come from?

Guilhem: We started our research during our studies at the Beaux-Arts. Our first intention was really just to experiment. We did not intend to make a documentary or a film in any way, but mostly just wanted to observe. The idea was to connect to a game and to go and see what was going on there, by observing, without playing. We weren’t really aware of what was going on in these online games at the time. At some point we came across a player who wasn’t using any of the game’s tools and was just hanging out. When we saw that this was possible, to stop in a game, to simply take in the landscape and look around, to sit down with people in a virtual world, to just pause, to talk about other things, to not play in fact, we realised that it was perhaps possible to make a documentary here. That’s how it started I think.

Ekiem: The starting point was also simply the idea of a meeting, to say to ourselves that in this environment, in the virtual world, there are meetings possible with real people, and we wanted to see if we could provoke them. This was the basic idea of our very first film, Marlowe Drive, but it was also the starting point for this film.

Your previous film was shot in Grand Theft Auto: V. Knit’s Island is shot in DayZ. Why did you choose this game?

Guilhem: We initially wanted to make another film in GTA. But we quickly became interested in games where it was possible to talk directly from avatar to avatar, with spatialized sound, which reinforced this impression of reality or immersion. That’s what makes the meeting between two people so precious and special in DayZ. We’re on a very large map, with only 80 players, in a rather stressful environment. As soon as there is an encounter with people, player to player, it becomes extremely strong, extremely powerful.

Could you explain the principle of the game DayZ?

Ekiem: It’s a game that goes against everything we encountered in GTA and our previous film. GTA is a game that is deeply consumerist and really based on the imaginary American dream. With DayZ, we arrive in a game that takes place in a kind of desolate, post-apocalyptic countryside, which is located in Eastern Europe. It’s a survival game. Contrary to a game where the goal is to collect cars and luxury apartments, here, you simply have to try to survive alone or in a group, to build your cabin in the woods. We are in a fairly realistic simulation where you have to find food, water and medical supplies to survive, and where interaction with others is essential. It’s really the antithesis of what we wanted to explore in Marlowe Drive.

Quentin: After Marlowe Drive, we realised that we had only interviewed individuals, alone, and we went looking for games where people would gather in groups. It sounds a bit paradoxical with what we just said about DayZ, but I remember a video of René, one of the characters in the film who set up a community and was making videos on YouTube at the time, talking about how people were getting together and building stories together. I think we were really attracted by this story of gamers who get together to do things, who don’t fit this stereotypical individual concept of a gamer.

How did you divide the roles during the shooting?

Ekiem: In Marlowe Drive, I had already started talking to people and meeting them. I was the intermediary between the audience and the players, with the idea of recreating this classic documentary interview device. We used this idea in the film.

Guilhem: The film crew was quite small. It was just the three of us. We were all wearing several different hats: those of director, journalist, technician and cameraman. The roles were all taken on quite naturally. Ekiem was the main contact person, Quentin the first cameraman and I was the technician. These roles were useful outside the game and inside. On a typical day of shooting, we started with the preparation outside the game. We would contact players on the messaging platform Discord, to find out where they were or where on the map they were going to log in and where we could meet. Then we would prepare a series of questions in relation to those encounters. Once inside the game, it is absolutely necessary to find food, drink, clothes, and light. You also have to avoid getting sick, find medicine, you have to be prepared for any eventuality in order to last. An interview would last four, five or even six hours. And that requires a lot of preparation. The simple fact of getting to a shooting location also took us a lot of time. It happened quite often that we were two or three hours away from our character.

Ekiem: Because it’s a parallel reality, there’s also a different day/night cycle. We never knew if we were going to shoot the scene during the day or at night, on which server, etc. It required a lot of organisation too. We had to prepare our avatars on several servers at the same time, to be able to be at the right place at the right time, with enough resources to survive for at least a few hours. We also had to deal with all the mechanics of the game and the updates that sometimes complicated our work. I remember at the very beginning of the shoot there was a very annoying update. The developers added a breath cloud when it was cold. So there constantly was this fog in front of everything on the screen when we were shooting. We had to adapt to that. Our camera character Quentin couldn’t get cold. So we constantly had to make a fire next to him so that he was always warm and could film without this fog. There are lots of anecdotes like this from the shoot. At times Guilhem had to kill two or three sheep in a hurry, because otherwise the camera or my avatar would starve. Our avatars were like living puppets that we had to feed in order to keep doing our job.

Guilhem: After a while everything got mixed up. We stayed locked up for three months, there was Covid and so on. It was quite strange to be in this bubble for so long. Sometimes we would eat in real life and then we would go back to the game to shoot and we had to keep eating in the game.

Ekiem: There was a bit of a double life thing going on. For me personally, it was one of the strangest life experiences I’ve ever had, at least in relation to other people. We lived through very special moments that we could never have planned. Precisely in relation to this story of a double life, where you have to maintain yourself and at the same time maintain this virtual character in order to make the film. I think that this is something quite unique and it was spread out over so much time. We realised afterwards that it was a part of our life that we had put in there. It’s a thought many players who play a lot have: there is a part of our life in this place.

Quentin, how did you experience this as a cameraman?

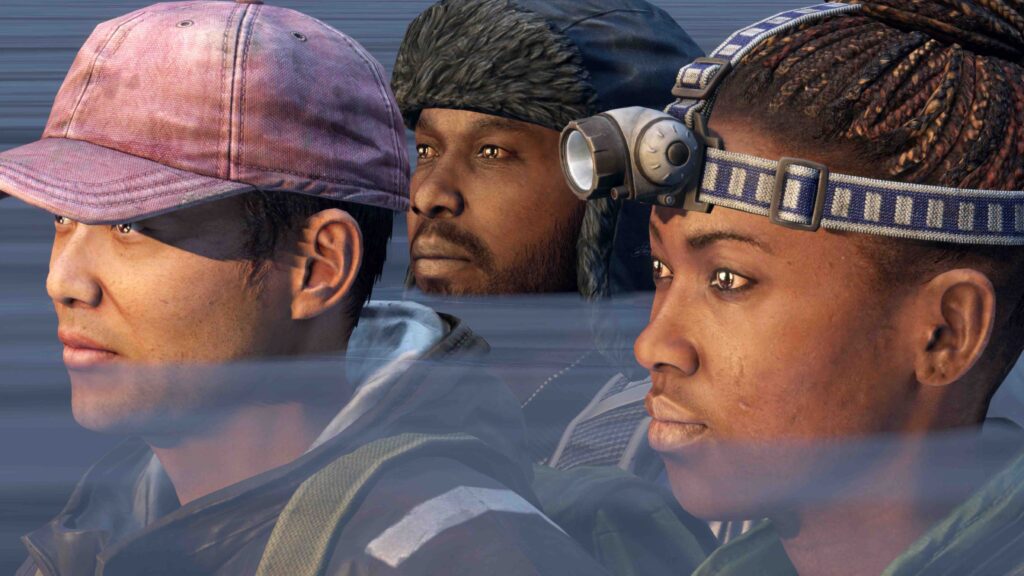

Quentin: What was complicated was the avatars I was filming are a kind of puppet with very few facial expressions. So the challenge was to film something that doesn’t have much life or that only has life through sound. There was also a somewhat strange relationship of distance to the other, which is inherent to the game. In real life, you keep a distance from someone you don’t know well, and you have to respect that in the game, too. If I had to get really close to someone to get a close-up for example, which I had to since I had only had one focal length, I couldn’t always do so. Gradually in our adventure, as we got closer and closer to the players, I was able to get physically closer to them. By the end, with characters like the Reverend, I could be completely glued to his avatar and there were no concerns from his end.

At the beginning of the film, you see mostly role-playing. As you spend more time in the game and get to know the players better, they talk more and more about their lives outside the game. Is that an illusion that is created by the film or by the editing or is that something you really experienced?

Ekiem: It’s reality. It’s also an account of an experience that the players have on their side. First of all, between them, they are playing a role, and little by little all that crumbles down to make room for things a little more intimate. And so they become this double character. The avatar with a real person behind it. As time goes on in the game, you feel more and more ready to open up and have a real relationship. And I think that is what happened to me, as the one interviewing them. These people, I had to invent faces for them, invent lives for them. They gave me some elements, some snippets of their personality and I tried to recompose a portrait in my mind. It’s also funny because after a while of playing, the players can recognize each other even without speaking, just by the way they dress and move their avatars, by their attitude. I think that all of this helps to create more and more real bonds. And that’s what you see in the film. You start with something that looks like a play, something that’s being played out, and gradually you meet the people behind these actors.

Guilhem: We found a group of people who had already been playing together for many years, some for 5 years. Most of them were hardcore gamers who were into roleplay, they challenged each other, they were very involved in the game, they spent a lot of time in the game. We met someone who has already played for almost 20,000 hours. When you’ve been playing for that long, you end up going into the game just to talk and you end up revealing things about yourself or just asking what you did all day.

Many players insist on the contemplative side of the game. We have the impression that it even becomes a substitute for some of them to go for a walk in nature or to relax.

Guilhem: DayZ is a game where it takes hours to go from point A to point B, to meet someone, to talk to them. It always fascinated me to see how we were playing a game that was ultra technological in terms of how it worked, etc. And in fact, people sometimes take it for granted. And in fact, people sometimes take an hour and a half out of their game time to go knock on their friend’s door, to see if they’re there or not. Instead of sending them a message on Steam or some other messenger. There’s an idea here of really taking your time, as opposed to what we see today in terms of speed on the Internet.

In these communities of players, it is sometimes difficult to integrate, you have to show your credentials. How did your integration go?

Guilhem: It took a while actually. We hung out on the server I would say for about a year. And at some point, people knew us. We had explored enough, played enough. We had died enough on this server, we had struggled enough to be recognized by the players, who then respected us as documentarians. We got our pass, so to speak. With this pass people didn’t kill us anymore. It was nice actually, going from one group to another. We even went to see people who were sometimes very violent. But we were protected.

Ekiem: There is also a language that we didn’t know much about at the beginning, the language of video games… It took us a while to understand this jargon.

Guilhem: They understood that we weren’t there for fun. That we were there every day and that we would walk for 3 hours to come and see them. They understood that it was real. This real dimension of our documentary transcended our relationships there.

At one point, you almost become a driving force in the film, you suggest for example to the players to go and explore the limits of the game. I’ve noticed that the film gradually explores these transitional spaces more and more. Was this your intention?

Ekiem: We wanted to film people who are themselves in a virtual place. And sometimes some people would reveal themselves by exploring the game, looking for glitches, bugs. So they were already in that position. It inspired us to go through this experience of walking into nothingness, which is quite symbolic. To become yourself in the game is also to get out of it, but you can also get out of it while remaining inside. This is a phenomenon that we wanted to film and that crystallises one of the bigger ideas of the film.

Guilhem: When you have gone around a game, you go and look for its limits. What else can you do with it? What are the possibilities? I think that experimenting and looking for these loopholes in the game code is part of the game itself, it’s like a new game within the game. There’s something interesting about the fact that the developers left this Out-Of-Bounds area accessible and infinite. You can walk in there forever.

Quentin: There was this film, Gerry by Gus Van Sant, that was running through our heads when we started preparing this sequence. This infinite walk in the desert, which is a kind of quest for the absolute. We launched it in a rather naive way, we said to them “come on, let’s walk until we die”. So, death, there, is the disconnection. At this point in the film, we wanted to offer them something that would allow us to film them just with an onboard camera, to say “OK, we’ll see how they react, how they talk to each other”. In fact, it wasn’t so obvious in the game to film them talking, to have this intimate moment. This space, which is at the same time infinite and behind closed doors, allowed us to be close to them to capture these moments.

Can you describe your filming setup? What were the biggest challenges you encountered?

Guilhem: I think all three of us wanted to see how we could push this shoot a little further than a streamer filming himself playing. The most important thing was the fact that we had the possibility of filming together. So we played as a team, we could have several camera shots and therefore a great diversity of shots. Then, the technical challenge was also to be able to separate the sound of Ekiem’s voice, the players’ voices and the ambient sound, which the game does not allow natively. We set up a system where each director’s computer would record one of these elements, we would then send it to our mixer and then back to our headsets, so we could hear all combined. When editing, it was very useful to have separate tracks, which is impossible when filming in real life.

The technical challenges were mostly to keep the camera going. The camera is an avatar that has needs, like water, meat, and especially medicine so that it doesn’t sneeze, because otherwise the camera moves all the time, it’s a hell of a thing. And if the avatar has lost blood, the camera switches to black and white. So we had to be very careful with that.

Did Covid influence the making of the film? And the behaviour of the players?

Quentin: It was something that actually followed the second part of the filming. We could see the pandemic spreading and arriving in Europe. There was a mirror effect that was a bit strange for us, playing in this post-apocalyptic universe, with diseases present in the game, going to get medicine, covering ourselves with clothes… And the reality that exceeded the fiction…. Then there was the lockdown in France, which happened three quarters into the shoot. We wondered if we would be able to go home, each on our own, afraid of being blocked, of not being able to continue the shooting. We took a chance to continue together. It was strange to take a break from real life, a break from this life that we also missed a little. But all of a sudden, everyone was taking a break too. Everyone was going to be locked up at home too.

Ekiem: Everyone was forced to go through what some of the players are actually going through. It’s a parallelism with the film project and the game, the fact of being at home, which we translated into the scene with the windows. The characters are in front of virtual windows and describe to us what they see at their window, at home in real life. We had written this scene before the lockdown. And when the Covid hit, it was echoing. It’s something we hadn’t planned and that in the end gave a lot of scope to the film.

Do you still play DayZ? Could you imagine going back?

Ekiem: Not alone anyway.

Guilhem: Maybe the three of us could go back. But I wouldn’t go back alone. It’s either with Ekiem and Quentin, or not at all.

Quentin: During the shoot we dreamt of organising a screening inside the game for the players. It would make sense to go and do that. But otherwise, I think that right now, no.

Ekiem: We started playing this game for the movie. It’s something very different than the simple purpose of entertainment.

Guilhem: In fact, if we go there, we will want to film. We can’t just be players there anymore. I think we have a certain distance to this game, the players… A distance that was necessary for us to make the film, to make this documentary. And it’s important to keep that distance.

How did you choose the title of the film?

Ekiem: When we made Marlowe Drive, we chose the title of a place, a territory. We found it interesting to try to name this place, to give it an existence. Knit was a character that we invented, an explorer… We kept this idea. I had also heard about ghost islands, these islands that we find on Google Maps and which do not exist, which are bugs. It reminded me of the world of video games. For us, virtual places are still unexplored excrescences of our world.

Guilhem: Knit, in a way, doesn’t mean anything at all. I think we all have a hard time defining this virtual world with precision. Knit’s Island is the island of something, we don’t know what. That’s what we liked about the title, something indefinable.