Neil Young in conversation with Tim Leyendekker

Feast is largely inspired by the real-life Groningen HIV Case which hit the Dutch headlines back in 2007. Do you remember your first and subsequent impressions?

It was quite a big story at the time. We have a populist newspaper in the Netherlands, De Telegraaf, and their front pages had big stories about “HIV Monsters.” Needless to say, like many people I was very shocked when I read about it. It stayed with me much more strongly than other news events.

In the days that followed more information was published. I read that the people involved had jobs: one was a bartender, the other was a nurse, one was an account manager at an energy company. You realise that it’s not possible for a monster to have such an occupation. I became more interested in what the motivations for their criminal activities could have been.

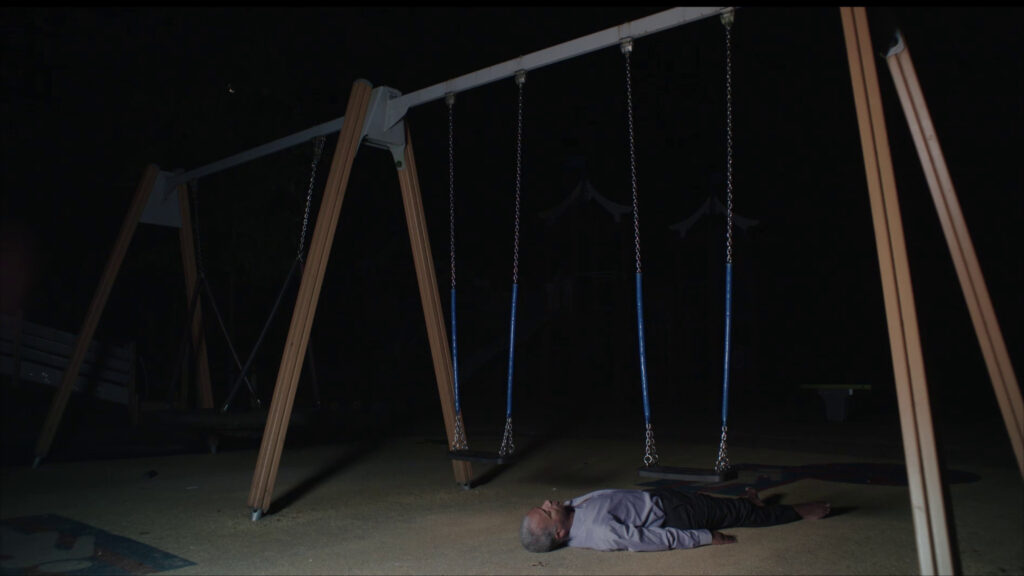

Later on it became clear that some of the plaintiffs had been returning to the parties despite feeling that something had been wrong, that they might have been abused without them fully realising it. For instance, one of the accusers said he remembered being totally drugged out even though he’d only had a few beers. He woke up the next day in a park, without remembering how he got there. So my question was not just about why the perpetrators did what they were accused of doing but also, what motivated those victims to go back to a place where they’d been harmed?

So my question was not just about why the perpetrators did what they were accused of doing but also, what motivated those victims to go back to a place where they'd been harmed?

The first sequence shows a police press- conference in which items found at the crime scene are laid out on a desk. The film itself operates similarly: you lay things out individually over the seven sections, allowing us to assess different aspects in isolation. This approach of compartmentalisation is something we find in your various works over the past 20 years, and again here in your first feature-length film…

What interests me in isolating these sequences in this way is that it gives the viewer potentially more freedom to engage with it, with the film, with the case, with whatever’s on the screen. On a more personal level I’m interested in what happens if you see something and it’s not so processed yet, meaning that as a viewer you have more freedom to interpret it the way you want.

What interested me about the laying out of the evidence, in the first sequence — this really happened in the Groningen case — was that they only showed objects which they saw as relevant. But what would happen if you really wanted to tell a fuller story? Maybe it’s then interesting to also include objects that aren’t directly part of the crimes which have been committed. I really like this idea of quasi-objectifying things so that people get the feeling they can relate to the narrative in a freer way.

The seven sections begin with the press- conference and end with one of the victims lying unconscious on a lakeside beach. How did you go about ordering these sequences?

When we applied for the production budget the Netherlands Film Fund were a bit afraid that it wouldn’t cohere, that it would feel like seven related but separate stories. One of the conditions for getting the production money was working with a script coach.

At first I was a bit unsure about this, because funds can be pretty traditional and I didn’t want to

work with someone who’d want to impose more of a traditional narrative structure. But then they gave me the freedom to choose whoever I wanted. I asked Koen Haagdorens, dramaturge of NTGent, a theatre-company in Ghent, Belgium. It was really good to work with him. After many conversations it confirmed that the original order I’d come up with was the right one.

The main thing we did change was that the figures of the men lying in the landscapes would all have been one single sequence, but we decided to split them up and interweave them as a connection or punctuation between all the other scenes. This helped to bring it all together, make it more of a whole.

In terms of collaborators, you worked with seven different cinematographers, with a wide range of experience. Why did you choose that approach, rather than working with one DoP and asking him or her to devise seven different looks or moods?

I was really looking for very different voices and visions, and it was quite a process to find this group of cinematographers, who have such a range of looking at things. The invisible backbone of the film is the text by Plato, The Symposium, or The Banquet as it’s sometimes translated in English, where you have seven notable men, and more indirectly one woman, Diotima.

They talk about what Eros is, or can be, and they all have a monologue, it’s a bit like a game or a competition and Socrates is in charge of things, you could say he’s the referee. Everybody’s looking for

the best definition of Eros, whether it’s truth, beauty, and so on. And Socrates ends the banquet with his monologue, saying that everybody did a great job, and delivered these lyrical definitions of Eros, but nobody got it right. He says everybody wanted to find the truth, but it’s not possible, because the truth is always in an elliptical movement, and it will always remain so. It’s very simple, his idea that it’s not possible to grasp something and pin it down as the truth. And this was also what motivated me to work with seven different cinematographers, to find out how they would look at that truth, knowing that it would influence the process and eventually the whole film.

The film works on two main levels, the Symposium level of timeless ideas, and the very specific real-life case. The sequence with one of the participants discussing the events, Hans, seems like documentary testimony…

Yes he’s the actual person, one of the people who were convicted. It took me a very long time to get him to

talk into a recording-device. I wanted to use his actual voice because I’m interested in how this slice of reality resonates within more fictionalised situations, in seeing how this bounces back, how it fits into what is a very precisely-controlled overall construction.

I’m keen on getting these different realities and mixing them, making the viewer consider who is a real person and who is an actor playing a role. This whole idea of what’s real and what’s not, I find it interesting that this is something people are questioning throughout the whole film. It’s something which isn’t just a concept, it’s something that’s very much constantly present, something that activates you as a spectator on different levels. It means that you don’t just watch the film but that you’re also conscious of what you’re watching. But not all the time, that would be too much.

The sequence with the microbiologist in which she discusses viruses and their operation now seems very topical. And the way she talks about viruses, where she says “I don’t believe in bad and good guys,” again links the physical and the philosophical which is a running theme of the film.

I was fascinated by the words she used about the transmission of viruses in plants. She says “it’s like a gift,” for instance, and it made me think of Bugchasing parties where people give each other HIV and where that’s called the gift, there was even a documentary made exactly about that. I was very happy with the way her vocabulary seemed to connect with and recontextualise other aspects of the film.

Are you hoping to spark certain debates or reflections among the audiences the film will reach at Rotterdam and beyond, and make them think differently about the issues touched upon?

Maybe not so much people thinking in different ways, but rather thinking in a more active way. I would be very pleased if it caused people to think more critically about what they see and what they read. The subject- matter itself — I don’t really want to impose my own views about it, and I hope from the film it’s also clear that I don’t really choose sides. That isn’t what the film is about.

This relates to what I said before about spectators being more active or activated. I’m interested in people being more critical about what they watch and hear. That could be one thing they take away from the film, and I hope they will take that approach during the film also.