Five Questions to Philip Scheffner

EUROPE is your first film that largely moves away from documentary and heads more into the direction of fiction. Was that a conscious decision already at the beginning of this project?

I don’t know if that’s really true – “documentary” and “fiction” have never been opposing pairs for me, but are rather integral and interwoven components of my experience of reality. I think there are also many levels in my other films that open up an in-between space that extends into the fictional. The difference is perhaps that in EUROPE the question of “fiction” and “fictionalisation” is central. We – that refers to the author Merle Kröger, Pascal Capitolin, who supported me in directing, the producer Caroline Kirberg and Volker Sattel on the camera – have very concretely dealt with conventions and working methods of fictional film, questioned, dismantled and (re)appropriated them.

The basis of the film EUROPE is a documentary research based on the biography of the protagonist Rhim Ibrir. The confrontation with the reality of her life led inevitably in the direction of fiction.

You met the main actress Rhim during the research for HAVARIE. When was the moment when you decided to make a film with her and her story?

For the film HAVARIE, I shot documentary footage with Rhim. Conversations in the park, situations in the kitchen, walks through the neighbourhood. In the process, I learned a lot about her biography, the place in France where she lives, her friends and family – it was a very intense encounter.

Due to the conception of the film HAVARIE, I then only used part of the recorded sound and nothing of the image. This was the right decision for HAVARIE, but it left an ever louder voice in the back of my head to deal with the material again. Merle Kröger and I were simply fascinated by her presence in front of the camera. By her quiet, withdrawn and yet intense charisma and the strength and pride with which she lives her life. Working together on the film HAVARIE had created a basis of trust that we could build on. This enabled us to try out things that were new to all of us.

The film follows a clear aesthetic concept, which, as with all your films, is always very strongly linked to the narrative. How can one imagine your approach?

The aesthetic concept, as you call it, arises from the examination of the subject matter of the film. I see it as a reflection with cinematic means.

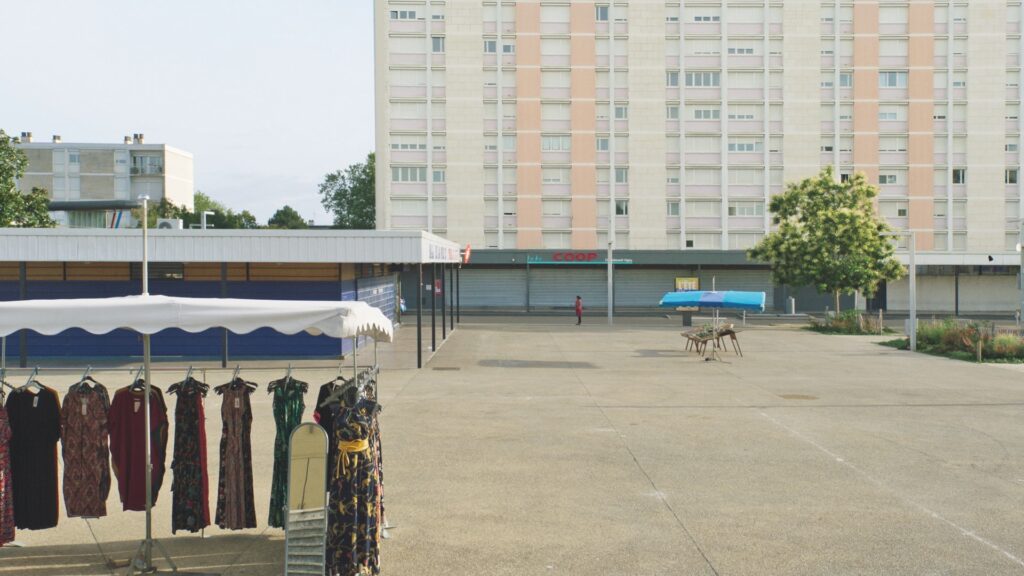

The protagonist of the film has her residence permit revoked. First of all, this means the withdrawal of a common social space. The space in which people can meet is separated along state decisions. Borders are drawn that massively restrict the scope of action of the people concerned and place them in a space of social fiction.

How can I make a film with a person who is not actually allowed to be there, whose real presence on location is therefore actually fictitious?

The logline says that EUROPE tells the story of a “state-enforced fictionalisation” (forced fiction). Can you tell us how this came about and what it means for you as a filmmaker?

I realised that working with classic documentary methods would have obscured Rhim’s real life situation: How can I make a film with a person who is not actually allowed to be there, whose real presence on location is therefore actually fictitious? This forced fictionalisation is constitutive for her personal life reality but also for her encounter with me. There is a border between us that cannot simply be dissolved by “talking about”. Therefore, together with Merle Kröger, I decided to examine the methods of cinematic fiction for their relevance in relation to the protagonist’s life reality and to see what scope this could open up. Rhim became Zohra …

Did anything change in the collaboration with Rhim when the film became fiction?

I believe that the preoccupation with fiction has above all led to a great openness. Positions and relationships could be playfully renegotiated.

The discussion of the script, the intensive rehearsal work and ultimately the shooting itself have repeatedly opened up other perspectives on both the personal and the political situation – for me, for the team and of course for Rhim.

Rhim has appropriated this space of fiction, conquered it. She has filled it with new facets of herself. Rhim became Zohra and both influenced and changed each other – the transitions between film and reality blurred.

Rhim herself describes this very clearly: “The film doesn’t stop – even when she (Zohra) leaves the film, she still lives what she played before.”