Directors in conversation

BLAKE: This is more of a comment than a question: we worked on this movie for a really long time.

SOFIA: Yeah!

BURAK: Very long.

SOFIA: Burak, I called Blake the other day while I was back in Juliane’s apartment building. I saw that her “Maison du bonheur” doormat was gone and I realized that I’d been putting aside all of my grieving for her so that I could focus on making this film. Now it’s done and it finally hit me that she passed. I can’t believe how empty her neighbourhood feels now.

BLAKE: I’d be curious to hear how both of you used this film to process grief. Sofia, this is the second consecutive movie that you’ve made while grieving over the death of a friend, and on top of that both of you were going through pretty significant breakups while we were developing and making it.

SOFIA: With Point and Line to Plane, my experience was an intellectual kind of grieving, and by that I mean I responded by trying to pursue higher knowledge. I was trying to understand something terrible that had happened by falling down a rabbit hole of art galleries, pursuing coincidences, trying to organize and make some sense of it. But I think because Juliane’s passing came so soon after Giac passed away, I didn’t have the capacity to manage it in the same way. I couldn’t process it by making something clever or beautiful. Burak began sending me his video letters as part of a correspondence project we agreed to do, but I couldn’t talk about anything. I didn’t have the mental bandwidth to respond or reciprocate.

BURAK: For me there is a huge difference between this and the films I did before. The videos I made at the start for Sofia were mostly a way for me communicate. I was struggling with a breakup, and I needed to talk about it. I never cared about whether the videos I sent her were good or bad. It was just about expressing something and being honest. I actually had never seen any of Sofia’s previous films when we started our correspondence. We were both in Berlin for the Berlinale in 2020, one year after we met there to present our own films in the Forum, and we met in front of the stairs at the Kino Arsenal, and she told me a little bit about her breakup and the heartbreak she was feeling. It stuck with me, so when I was going through something similar several months later, I thought, “Okay, maybe Sofia can understand me.”

SOFIA: I was so paralyzed by the videos you sent. There was this very deep self-knowledge and self-awareness in them, and for me, seeing how articulate and poetic you could be while being in that state just made me see how drained I was. Maybe now that the movie is coming out I’ll be able to talk about it.

BLAKE: At first it was a little complicated for me to find a way into the movie, because you were both carrying such intense emotional stakes into your contributions. Unlike you, I wasn’t grieving over a death or enduring a break-up, so for a while I felt like I needed to search for something to grieve about, to create a balance between the three of us. This caused me to think back on losses that other people I know experienced, and I found myself trying to embody their grief vicariously by re-telling it. This led to my character’s account of my art instructor and her grieving over the death of her art hero, Nam June Paik. There’s also a kind of grieving in my Google Earth video, when my character visits Audrey’s neighbourhood virtually on his computer. For one, there’s something pathetic about missing a friend so much that you start to roam around where they live on an app. But it was also a way for me to dwell on the loss of my physical engagement with the world. I made that video in early 2021, so my separation from friends and family was—as it was for many people—very pronounced at the time. We were all stuck at home, only able to connect with each other virtually.

BURAK: Before the start of this project, you and Sofia were also sending video letters to each other, yes?

BLAKE: Well, we intended to, but we actually never sent anything to one another.

SOFIA: It didn’t work! Blake had two 3D cameras and gave me his spare one so that we could make a correspondence film with them, but it didn’t happen. I think part of the issue was technical barriers. Blake is the only one of us who knows how to edit 3D footage.

BURAK: Ah, okay. I didn’t know that. What I was going to say is, Sofia visited me in Berlin while I was working on more videos to send her and she said, “Stop, listen, I have another idea,” and she explained to me the story of our movie, with the details about Blake’s part and her part and my part, and how Audrey would be in these two correspondences but not able to respond to anyone. I thought it was fascinating and I said, “Oh, so you mean like this…?” and explained what she said back to her in my own words. I described some things she didn’t intend, and she said, “Oh, well I didn’t mean that, but I think this is great, too!” So the movie is the way it is because of failed communications, and due to things getting lost in translation.

SOFIA: The narrative line of the film took so long to develop. Not only because of the difficulty with communication, but also because of how long it took us to settle on what we all wanted to individually articulate with it.

BLAKE: I only finally understood what I wanted from the film at the end of the editing process. Of course, I knew from the beginning what the narrative structure would generally be, but my understanding of the film kept changing at every stage. It changed when I saw all the videos that Burak sent to Sofia, it changed each time I created a new video letter…

BURAK: It’s because the film is not about the story itself. It is really about the two years that passed while we were making it. For me, it was two really difficult years, I was at a ‘zero’ point. Not just because of the pandemic—it’s not a pandemic film, in my opinion—but because during that time we all just really wanted to communicate, and the only communication we had was through frames, like Zoom, or through a screen online. I felt like I was completely naked in the street, alone, with no idea where to go, and all I could do was hold my camera. It was the only investment I had in my life. I wanted to do nothing except record locations, record these landscapes. I wanted to share the landscape with Sofia through the videos, to say, “I am here.”

BLAKE: I really appreciated how, relative to the footage that Sofifia and I created, almost all of your footage was shot outside, in locations that seem quite distant from one another. When I look back at my footage I really feel the lockdown; I’m fifilming off of screens or through windows in my apartment, or using old footage I’d shot more than a year earlier. And Sofia shot a large portion of her footage inside her apartment, too; and, when she filmed outside, it was still within Paris. But you, Burak, it felt like you were roaming free. Some of the greatest sense of “escape” in the movie is contained in your videos because of that. You’re the one escaping the stationary lifestyle that Sofia and I were wallowing in.

SOFIA: What I was so impressed with in your letters, Burak, and what I found difficult to respond to in a traditional sense, was that your videos and your voice had this extraordinary way of showing your surroundings and how you felt. I was so afraid to articulate that, which is why I had nothing to say back to you. It was only when I threw on A Man Escaped one night that I felt like I might have a way out. I remember that it felt almost like a lightning bolt: I could use Bresson’s words to write a screenplay about my own escape. I think when my brain is fractured in the way that it was, I find my footing through whims and coincidence; even if the idea doesn’t make much sense, I start threading and braiding things together, the same way that Audrey does with the challah bread—just finding strings and making connections.

I’m curious, Blake, how you approached dialogue and speech for this movie. I ask because, while your films are often very intimate and personal, you tend not to feature actors or language in them, so, somewhat similar to me with this movie, you had to find or develop a way of communicating that maybe you weren’t comfortable with.

BLAKE: I think a lot of the intimacy that comes through in my work is a product of the fact that I tend to work in solitude. I’m not the kind of person to mutter things out loud to myself, so any dialogue that’s happening is a conversation I’m having with my materials and tools. It sounds cheesy, but the images I create can only communicate nonverbally, so the conversations I present on screen are nonverbal as well. The movies offer a voiceless exchange of information. Working on a project now that involves other humans, well…I couldn’t use that excuse! As you recall, I was a little worried about how my style of creation would behave when language became a more prominent part of the experience, which is why we briefly incorporated the narrative device that would allow Audrey to ‘mute’ my character; I’d send a video to her in which I told her about whatever was happening in my life, and, unable to bare the sound of my voice, she would quickly mute her laptop, and thereby allow my videos to exist only as silent images. But over the course of making the movie, I found ways to make it work, so we ditched that device. Much of my interest in cinema lies in the way the medium can show a logic system materializing and evolving visually over a period of time, so I tried to write my dialogue with this approach—starting with one idea, and letting it shapeshift, keeping itself afloat in accordance with whatever images it was placed with, or whatever the narrative situation was when it was being presented. I don’t know if what I ended up with is cinema or if it’s literature; it’s more like some kind of in-between mutant thing.

Part of why I like working with 3D is that the images also have this kind of uncanny, mutant quality, like they exist somewhere between realism and fantasy. For example, if I take a 3D photograph of an object on my desk right now, the image doesn’t really look or feel at all like what I see with my own eyes. It’s more like a dream of that object, of that image. Its volume and shape becomes a very forward part of the encounter, whereas when I look at the same object with my own eyes, the relationship is different. It’s just…there.

BURAK: I am sort of the same way, because when I make a film, I need the image to feel fake. While I’m shooting, the decisions are coming from inside me, they’re very honest. But the footage must become fake before I can transfer it to another person. Then the footage can be more present in front of your eyes, like it wants you to play with it.

BLAKE: By fake, do you mean the way you shoot in super crisp 4K digital, but then you make it look like it wants to be film?

BURAK: Yes, that’s why I change the framing, add round corners, apply layers of noise and colour—I really work on it a lot. I can’t show the raw material, because when I look at it I’m always so embarrassed. Not because it’s wrong, but because it is raw, too honest. I couldn’t send this material to Sofia until I made it fake.

SOFIA: I tend to work with 16mm because it keeps me honest. I have this method of process cinema; whatever happens while I’m shooting, any mistake that occurs, I’ll incorporate it into the narrative. I like to let mistakes mold and shape the film instead of hiding them. This shoot was particularly difficult because I was filming in Paris in the wintertime, so there was very little light. I was shooting on a wide lens that I wasn’t used to shooting with, and some of the shots came back a little out of focus. They’re very soft and fragile images, and when I first saw them I rejected them. I felt embarrassed and thought, “What’s wrong with me? How could I have not gotten these to look sharper?” I shot in two phases: first I got all these wides of Audrey’s day-to-day at home, and then I shot all the close-ups afterward. Because the film is about a person who is in this liminal space, she’s unsure of herself and her future, I thought there was something in the wides that could work. So for the close-ups of Audrey’s hands in the second phase of shooting, I experimented with intentionally racking the shots in and out of focus. You can really feel the hand of the cameraperson, as I’m trying to figure things out in that situation. I really love shooting on a Bolex because I make a mistake every time! Each time I learn a lesson, and this time the lesson was that it’s okay to be a little soft or fragile or unclear.

BLAKE: This was the first time you’ve ever shot 3D footage. Do you likewise feel some uncertainty in that material? Like a cameraperson trying to find their way?

SOFIA: You gave me the camera at a time when I was processing something very serious in my life, so the images I created with it document those moments of despair, chaos, and destruction. Watching the footage now there’s some understanding that comes to the surface. It was a way for you to step into Audrey’s shoes, and at the same time a way for me to hop into your shoes as a filmmaker. It felt like the future.

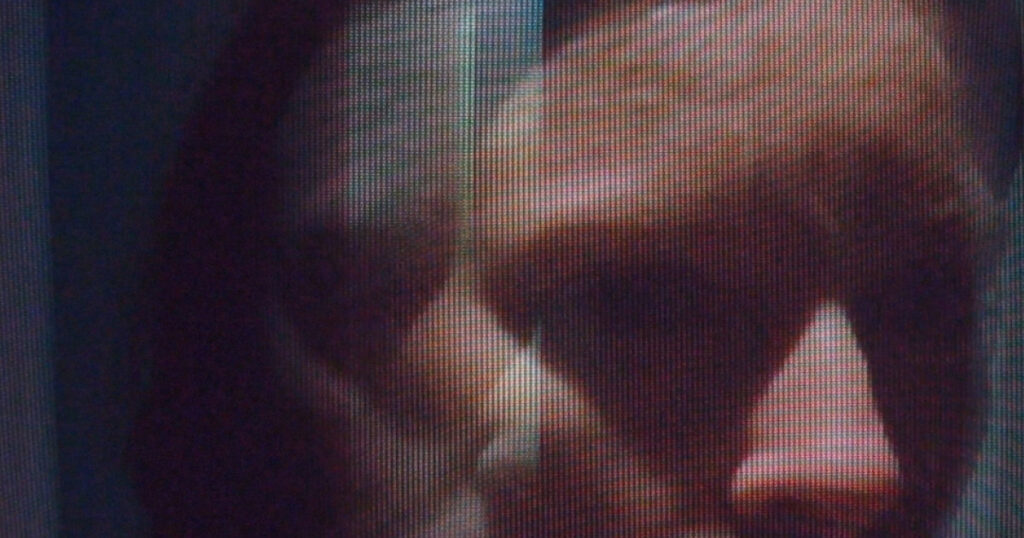

BURAK: When Sofia came to Istanbul last year to work on the film, she and I came up with this idea that Audrey’s character represents the present, I am the past, and Blake is the future. It may not be true, but that’s how we spoke about it at that time. Now, when I look at the film, I see the characters from the perspective of landscapes. I see in my character a landscape of grief. This is especially true in my last part, which I shot in the Armenian ancient city called Ani. The mountain you see is in Armenia, but I’m shooting it from the Turkish side. There is a lot of grief tied to that city because of the historical conflicts between the two countries, so these images evoke a political, historical, and also very personal grief for me. In Sofia’s part with Audrey, I see it as a landscape of resistance. There’s resistance to the daily routine, almost like Jeanne Dielman—a woman resisting her situation. She’s trapped at home doing the same thing every day, preparing food, checking mail, etc., and she must communicate but she doesn’t want to. She resists it, tries to escape. But Blake is like a landscape of hope or imagination. In his Google Earth video we watch something that we normally experience in 2D, but now there is depth, in the image, but also in the imagination. He goes to Audrey’s neighbourhood and he adds depth to it by imagining it differently, from his own perspective. Maybe this is just me, but I think the whole film is about these different kinds of landscapes.

SOFIA: I thought of Blake’s character as representing the future because of the fact that it took me a while to understand it. When I was in Istanbul, we needed to shoot more footage because we were trying to somehow bind all of our voices and interests together.

We’re all really, really different filmmakers! Our tones and the way we work and express ourselves are extremely distinct. With Blake’s Nam June Paik video specifically, I wanted to find a way to thread it through the entire movie, partly because its connection was so mysterious to me. So I started doing research on Paik, learning about the way he worked with televisions and the cathode ray. I spiraled into the history of the cathode ray and found out that it was the display for one of the earliest forms of computer memory—device called the “Williams tube”! So then I was thinking about memories, the memories that we wanted to create together, the ones that we were struggling with, the ones we wanted to destroy, and the ones we wanted to keep near. Maybe it’s a stretch, but it helped bind a lot of the film’s different themes and ideas together.

BLAKE: When you both started assigning concepts like the past, present, and future to different characters, I was resistant,because I’m generally opposed to metaphorical forms of meaning-making. I prefer when things represent themselves, when they’re not standing in for an idea. So when this direction came up, I remember one of the big negotiations the three of us had regarded what the movie was “about” for each of us. For me, it’s about three individuals reckoning with their relationship to the past, and how remembering the past imposes on their present situations. Each of them handles that burden differently, just as each of us interprets the movie differently.

SOFIA: That’s been the best part of working on the film with both of you. We sometimes had to calibrate ourselves to one anothers’ sensibilities, and we each needed to find our own framework, or lack thereof. You get to see all of our coping mechanisms.