A Thousand Fires

by Herb Shellenberger

A blazing inferno. Slowly-roiling flames emerge from darkness, as gradually shifting reds, yellows, oranges and blacks dazzle. A deep, low-frequency sound evokes an appropriately apocalyptic atmosphere.

A hole in the ground is penetrated by a long metal rod, with brown and white-specked earth surrounding the void of an unknown depth, the initial sound gradually receding into the background.

A hand and wrist—glistening as if covered by some viscous material—guides the swift upward movement of some kind of cable followed by a metal cylinder, brown-black fluid dripping off the hand as it steadies these materials.

With this thrilling initial sequence, Saeed Taji Farouky establishes the sensory and material experience of his feature documentary A Thousand Fires, along with its ever-present and lingering danger. The film focuses on the modest wells that comprise Myanmar’s unique, artisanal oil production market and centres the story of one family working within this industry that is likely unfamiliar to most viewers.

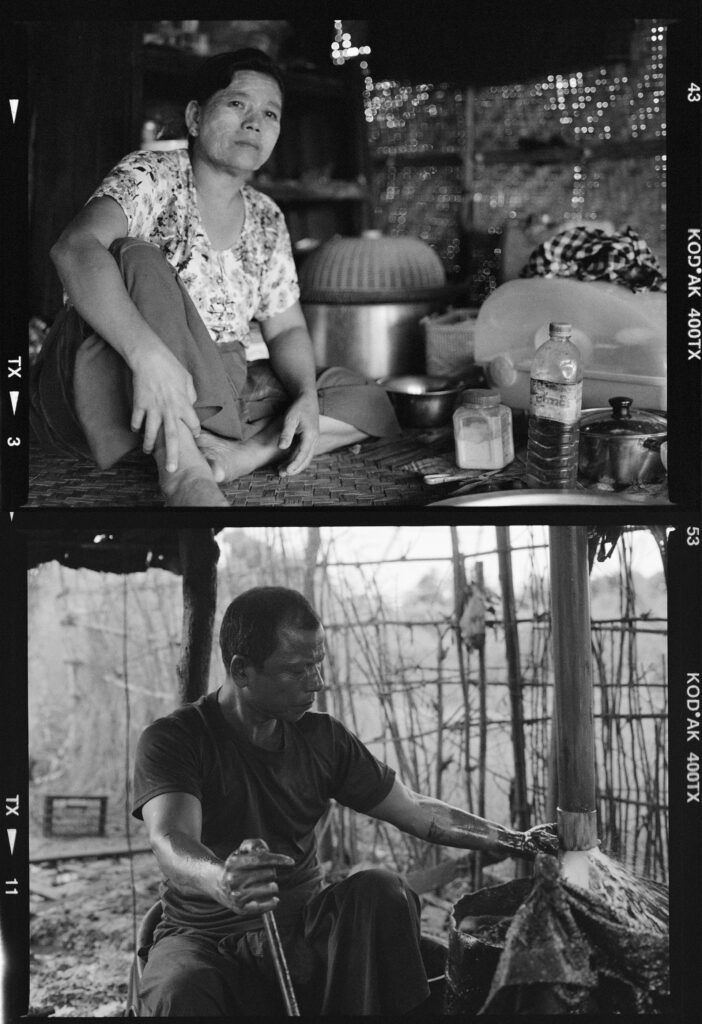

But A Thousand Fires doesn’t provide a wider background of the specific context of hand-drilling for oil in Myanmar. Instead, the film documents the experience of the family unit who undertake this precarious, potentially lucrative but risky and messy business with hopes to buoy their own financial situation and to hopefully provide a better life for their children. It is against this background that we encounter Thien Shwe and his wife Htwe Tin running a hand-cranked power generator, drilling meters beneath the ground under their small plot, draining the cylinder of water and oil and refining it to be sold to a vendor who will move it down the chain of production.

The work that we witness only begins with removing this viscous material from the earth. We come to learn the cycle of hand-drawn oil production: its extraction from the earth; the collection of raw materials; the separation and filtration required; its packaging into barrels or tanks; its transportation to the vendors; and finally the negotiation and sale. (The threat of combustion—a seed planted by the first image of the film—looms ever-present.) But as we witness this work, we discover it is literally a hands-on enterprise: “you have to do it by hand,” Thien Shwe tells his son Zin Ko Aung. He also explains, “it’s a new well, but we’re not getting much out of it,” relating the idea that plots need to be moved and new wells dug with regularity. In fact, much of the information that we capture from the film is gleaned through conversation, with Farouky foregoing narration in favour of observation: we learn through osmosis, through the time we’re spending with this family.

Moments of myth and metaphysics [...] are accentuated through visual and sensory sequences that transport the viewer away from the everyday and into scenes of abstraction, fantasy and metaphor.

As the viewer moves through the film, we realise that this work is only one strand that the filmmaker weaves through the film, which reveals itself as more a story of familial struggle, love and ambition. We see moments of down time, of eating together, of Thien Shwe and Htwe Tin’s daughter and her baby, of Zin Ko Aung’s reluctance towards high school and his parents’ growing unease towards his future.

We witness scenes that attest by extension to the societal importance of not only Buddhist religion but also fortune-telling and the Burmese zodiac in particular to how people in Myanmar make important decisions in their lives. These moments of myth and metaphysics, such as tales of dragon’s breath and underground fires, are accentuated through visual and sensory sequences that transport the viewer away from the everyday and into scenes of abstraction, fantasy and metaphor. But they are approached deftly and with care; rather than evoke these scenes as different registers from work, conversation and quotidian reality, the filmmaker incorporates them side-by-side, without warning and distinction, suggesting that they are merely different registers which can be looked at interchangeably with the more familiar sequences.

There’s no doubt that the filmmaker’s highly considerate filmmaking—which includes the duties of cinematography and location sound recording—incorporates lessons from all over the cinematic map.

It’s poignant to consider what Palestinian-British filmmaker Saeed Taji Farouky brings to the table in observing the lives of Htwe Tin, Thien Shwe, Zin Ko Aung and their family. Previous projects have taken the filmmaker to North Africa, the Arctic and the Middle East, and could be said to marry a politically-committed perspective with formal and technical innovation—or, in the same breath, a journalistic impulse with deeply felt personal connection. Depending on one’s connection to cinema, certain references could be drawn: A Thousand Fires owes as much to the patiently-observant documentaries of Frederick Wiseman as it does to Yasujirō Ozu’s signature tatami shot, as Farouky’s camera is often placed at floor level where the extraction of oil from the earth involves crouching on the ground. There’s no doubt that the filmmaker’s highly considerate filmmaking—which includes the duties of cinematography and location sound recording—incorporates lessons from all over the cinematic map: Farouky has led a radical film school in London over the past years in which emerging filmmakers are engaged in non-conventional forms of filmmaking through lectures, workshops and importantly screenings of disparate, radical and bold films.

But the connection between Myanmar and the filmmaker’s heritage—which might not have been apparent at the start of the project—has unfortunately become clearer in the intervening period: “In early 2021 the Burmese military staged a violent coup and the cities and villages I had come to love became the scenes of massacres and torture… My people in Palestine, too, experienced a surge in violence, and the film became a shared expression of solidarity between Burma and Palestine.”

A Thousand Fires illuminates that solidarity through the modest but beautiful visuals and propulsive score (by Fatima Dunn) that it wraps its participants within, lending a universality to their story despite the unfamiliar vocation through which they have chosen to make a living. Deep within the core of this film, we find—rendered through an earnest and captivating cinematic point-of-view—an abundant wellspring overflowing with hope, aspiration and love, which one hopes viewers will weigh against their own daily struggles, cultural myths and individual perspectives.

Herb Shellenberger is a film programmer, writer and artworker currently living in Pennsylvania, USA.